Written on 21st March 2025.

Thank you, all the anonymous people who work to keep our modern lives running. You let us have the things we need without us being aware of all the work it takes, and I'm grateful to you.

When I was a teenager I thought my dad had the most boring job:

5.1 Immediately the Bulldale Street circuit breaker was closed, the lights in the control room went out, there were noises from outside the control room, and one of the engineers was aware of sparking and flashing from the wall-mounted control panel, the engineers saw billowing brown smoke and flames eminating from the Bulldale Street substation, then an explosion was heard from the centre of the No.1 section of the switchboard at Yoker Ferry Road followed by extensive arcing at the switchboard.

5.2 Convinced that the whole switchboard was about to explode, the two engineers made their escape via the rear gate and Mr. Craig contacted a police patrol car near the ferry, asking them to relay a message to the Distribution Control Centre to have the grid incomers at Yoker Ferry Road tripped immediately. The police were also asked to keep the already gathering crowd back from the substation.

5.3 Mr. Cameron considered he could not safely get to the radio in his car, but Mr. Craig, having unsuccessfully tried two local telephones, finally got through to the Distribution Control Centre from a private telephone and asked the Control Engineer, Mr. G. McAllister, to "get the supply off the Grid transformers", and after a pause of around 20 secs., the Control Engineer reported that the supply to Yoker Ferry Road was now off.

"I was in the Windyhill Group Office on Tuesday, 4 March 1980. About 16.45 hours I observed a large column of smoke in the city in the Partick/Yoker area.

Some 5 minutes later, Mr A. Johnstone, Grid Control Engineer, rang to state that Yoker Grid 1 was "D.B.I.", (Don't Believe It), at Grid Control and Glasgow Distribution Control Centre reported it OPEN. Grid T2 Main Buchholz Gas alarm was also up at the D.C.C.

I reached the front door of the Group Office intending to go to Yoker when my attention was attracted by the noise of an arc and I saw a flash and smoke in Windyhill 132 kV substation in the area of the gantry about OCBs. 305 and 705.

"South of Scotland Electricity Board. Fault Incident at Yoker Ferry 132/11kV substation on 4th March 1980. Report of the panel of inquiry appointed by The Chief Engineer, Transmission/Distribution"

My dad spent his career working as a chartered electrical engineer with The South of Scotland Electricity Board (SSEB) - which became ScottishPower in the 1990s. I think control has since moved away from Kirkintilloch, and has moved back to the publically owned National Energy System Operator in a centralised location for the whole of the UK.

At 03.06 on Saturday morning November 8th, 1969 during a night of wind and rain, a lightning discharge caused flashovers on both circuits of the Strathaven-Kilmarnock/Ayr double circuit…the conductors between towers 11 and 14 on No.1 circuit were extensively damaged and only 1 out of the 6 conductors remained in the air. It was at this point, where the line crosses the Hurlford-Galston road that a car ran into the line, skidded and overturned…

The lightning surge on No1. feeder had caused the Kilmarnock super-grid transformer Red phase…to flashover. Since the feeder protection failed at Strathaven, the arc continued to burn…the escaping oil was ignited and the light from this and the arc could be seen over a wide area.

At 03.06 it was evident from the feeder flow and other metering indications that a severe fault had occurred on the system…System voltage indications were changing rapidly, the C.E.G.B. MVar transfer recorder went off scale thus showing a transfer in excess of 500 MVAr.

At 03.09 a message was received from Ayrshire Distribution Control requesting that the Kilmarnock/Ayr feeder circuit breaker, H115 at Strathaven be opened immediately to isolate the supergrid transformer SGT1 at Kilmarnock, as it was on fire. This was the first positive indication that the Control Engineers had of the nature of the trouble. At about the same time they received indication of loss of generation at Cockenzie, Hunterston and of the shutting down of Cruachan.

AT 03.10 Grid Control reaquested Clyde's Mill Control to open switch H115, but they were unable to do this as the supervisory equipment would not accept the operation instructions. Grid Control requested Clyde's Mill to continue to try to trip H115, not realising the cause of their failure to initiate the supervisory trip operation. In the meantime Clyde's Mill Control room fluourescent lighting failed due to the fall in system voltages.

The frequency fell to 49.8Hz and 275 kV. voltage to 200 kV. or lower, but Clyde's Mill could still not trip H115.

South of Scotland Electricity Board: Report of board of inquiry into 275kV system fault on Saturday, November 85th, 1969

I feel I must have been a hard to please teenager, wanting something more exciting than explosions, cars overturning, readings going off the scale, and control rooms being plunged into darkness.

I'm writing this on a day when Heathrow airport is closed to due what appears to be a major fire at (possibly) a 275,000V substation. It prompted me to think of my dad's work and wonder what he would have said about the fire. It made me think of the fault investigation documents he had kept, from which I quote above.

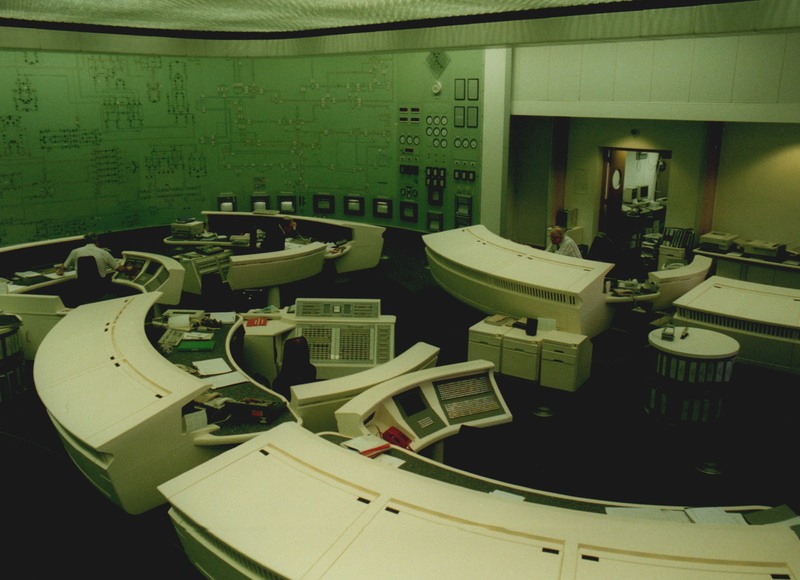

SSEB Grid Control

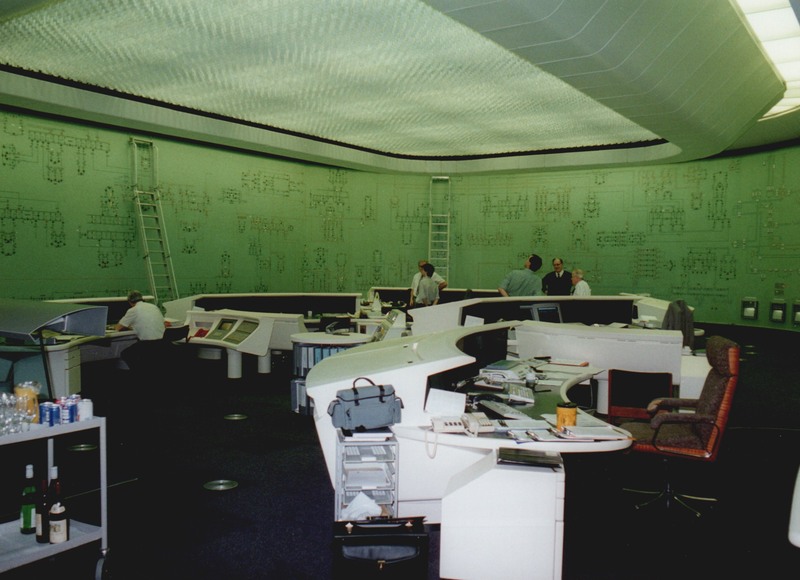

Much of the drama above would have occured in this room:

This is a picture from the early 1990s of the Control Room in what was known to me as "Grid Control" - a building in the countryside outside Kirkintilloch, near Glasgow. The people in this room had the responsibility of ensuring that electricity supplies in the South of Scotland were reliable, a job which they did quite successfully - apart from the occasional incident.

The room was surrounded by a giant schematic diagram of the grid system - pylons, substations and power stations. Warning lights would light red showing problems, and power lines would be switched in and out by moving switches on the wall. The diagram was so large it had a ladder to climb to reach the top parts.

The red telephone at the desk in the foreground was the emergency telephone - if you phoned the emergency number on a pylon it would ring here.

The giant machine

In the UK we take electricity for granted - we press a switch and the light comes on. But this comes thanks to what might be the largest and possibly most complex machine we have - a huge machine of generators, transformers, pylons and wires that span the country.

What's even more amazing is that this machine has grown over a timespan of more than a century, yet it has never been switched off. It's been going for so long that nobody really knows for sure how to get it going in case the worst happens - a country-wide blackout.

Getting it going again in this case - a process known as "Black Start" is fascinating in itself. They used to plan and rehearse black start at Grid Control, but fortunately never had to put these plans into practice. The problem is that the power stations need electricity to run - so how do you power the power stations when there's no power?

Why tea means it's important to watch TV at work:

A difficulty with electricity is that it's really hard to store. Battery technology is advancing, and huge grid batteries are being built, but the generation of power still has to be matched to the demand. The UK still has a number of large gas fired power stations, which have big spinning generators. If you keep them going and everyone switches off their lights they will spin faster and faster until they spin out of control leaving a trail of destruction. Keep loading them up more and more and - like my attempts to cycle up a steep hill - they go slower and they risk being damaged. So the amount of generation and demand must be kept pretty much equal.

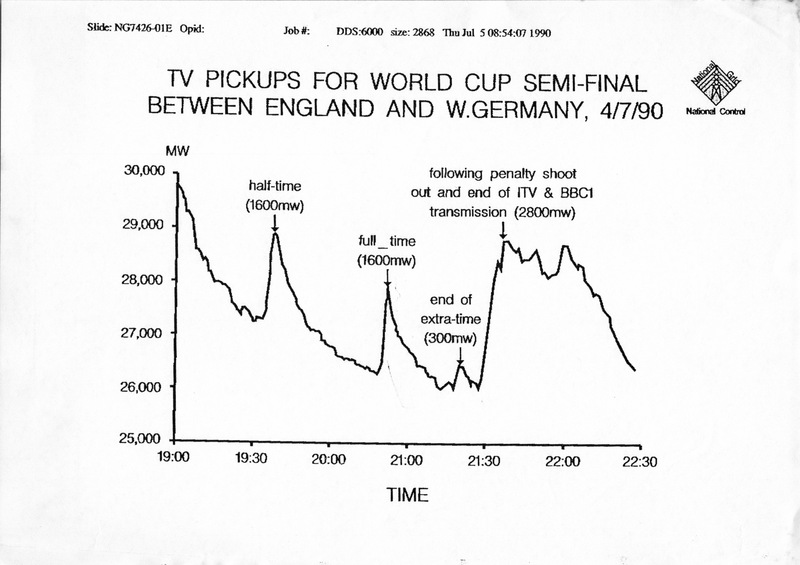

Apparently this is made harder in the UK due to our obsession with drinking tea. Any slight excuse during a TV programme and people will get up to have a cup of tea. Come the next adverts, sewage pump demand would then pick up due to…biology. This had a name: "TV Pickup".

Grid Control had to estimate this, and be ready to tell power stations to ramp up the demand. I remember the control room had a TV - they would be on the phone to a power station waiting for "Dirty Den's" bombshell and Eastenders to end. (If you're old enough to know what that means).

Figure 1: That's what they told me anyway: It's not like anyone would really be wanting to watch football at work.

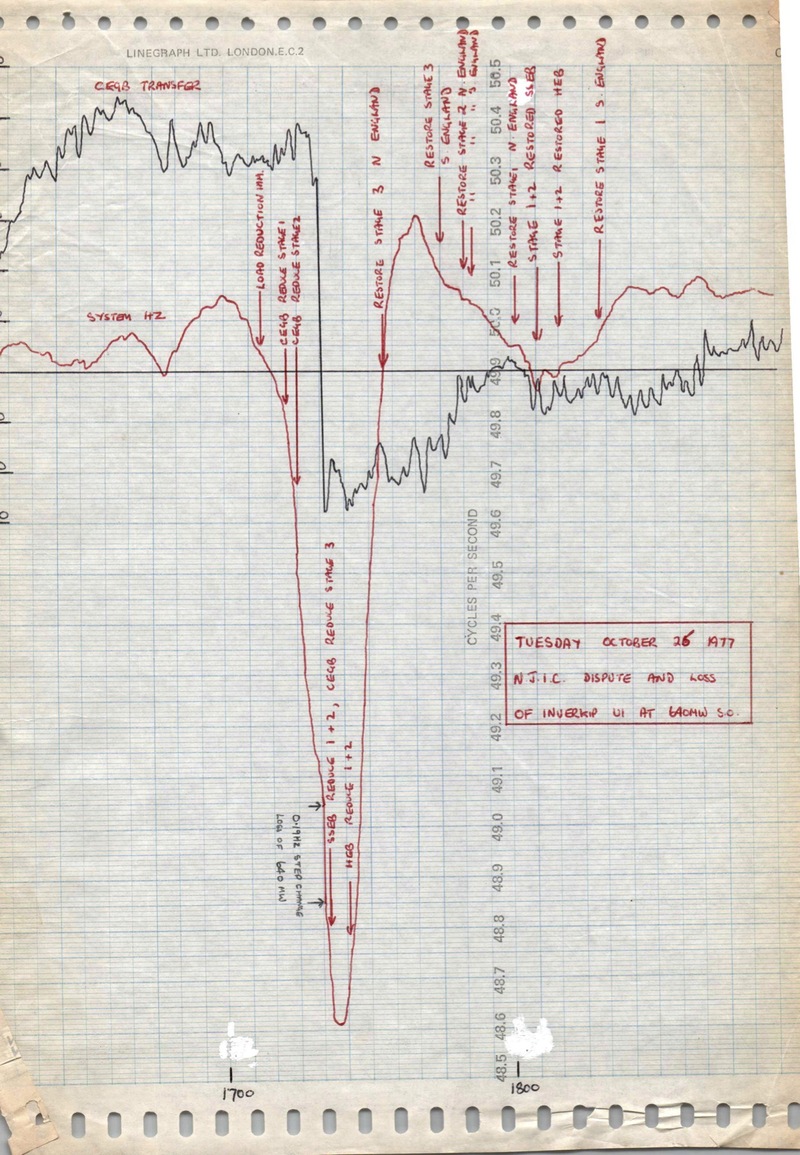

Power engineers love looking at the "frequency" of the grid as they can tell you its "health". In the UK it's supposed to be 50Hz but if it's lower then there isn't enough generation; if it's higher there's too much. The grid frequency was recorded by large chart recorders in the control room - before the days of computer storage - a pen would plot the frequency onto paper for analysis in case something went wrong. I love learning about these pre-computer ways of data storage and analysis.

System planning and maintenance

Another part of grid control - the section that I believe my dad mainly worked in - was planning for maintenance and future growth of the system. They designed the system such that it had capacity in case of day-to-day maintenance events, or in case of problems. I think it might have been designed to have "N+2" (I think) redundancy - in theory it should work if two things fail.

They would think about how demand would increase in the coming years, what would need maintained, what new power lines would be required, and how to plan and cost it all.

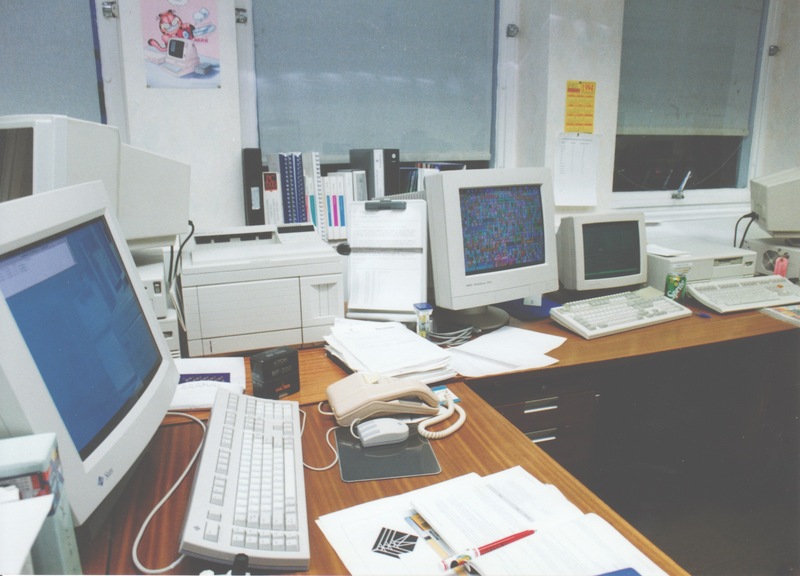

To help achieve this they used computer simulations to test various scenarios and ensure things should still work. They had (in 1994) the latest tech - Sun Microsystems Sparcstations and a DEC VAX. A 19" monitor on your desk, and a CD-ROM? The stuff of dreams.

Figure 2: Garfield: Proof that people loved computers as much in 1994 as they do now.

A calling

I believe that the people who worked there felt that it was a bit of a calling, and a important role, serving society. The various power generation organisations were a community who would help one another in case of a problem, by sharing information or parts. I remember hearing once about some specialist bolts being sent to a power station in the north of Scotland via a taxi from London. (The cost of the taxi was miniscule compared to the cost of shutting down the power station).

I think the move to privatisation in the 1990s ruined this feeling, and it was hard to adjust to. Instead of being a community, the engineers were now in competition with one another. Information about a fault was no longer to be shared, as it was now a competitive advantage. You were no longer serving society, you were making the most money you could.

Irn Bru and red wine: That's how you know it's Scottish

But despite the hard work and the difficulties it looks like there was fun to be had too. This photo was taken during the last shift of an engineer who was retiring. But look what's on the drinks trolley in addition to the Irn-Bru….

Thank you, everyone who works hard to keep our lives running.

There are many people who work quietly and tirelessly behind the scenes to let us have the day-to-day lives we have. It's only on days like today (The BBC are currently running the headline "HEATHROW SHUTDOWN CAUSES FLIGHT CHAOS AND LEAVES THOUSANDS STRANDED") that maybe some of these systems come into our view. Sometimes these hard-working people get villified when things go wrong, but not thanked for the 99.9% of the time when they go right.

So I want to thank all those people, and I hope my little "practising writing about things" blog post sheds a bit of insight into some of the work needed to keep all these systems going.

Thank you.

And they all lived happily ever after.

04.45 System frequency and voltage now normal. Agreed with National Control to come to a programme of import 200 MW to SSEB as generation built up before restoring load shed. Distribution controls instructed to commence limited restoration. Restoration of load in the Leeds area now almost complete.

05.00 Arranged programme of import 200 MW achieved. MVar transfer, system voltage and frequency all normal. Cruchan unit No.2 on load. Generation building up at Barony, Bonnybridge, Clyde's Mill, Dunfermline, Galloway Hydros, Portobello Generating Stations. SSEB import from HEB hydros 475 MW.

05.15 Load restoration proceeding (completed 05.50 hours) First estimates of generating plant expected to be available for the morning peak showed a substantial deficit. The CEGB stated the maximum transfer to Scotland that system stability could allow would be 900MW. A pessimistic estimate put the deficit at 1300MW and as a precaution a warning of four stages of load reduction was issued. This warning was subsequently modified to a warning of two stages of load reduction, as more generating plant became available.

No voltage reduction was necessary and the breakfast peak was met with a deficit of 345MW which was imported from the CEGB.

South of Scotland Electricity Board: Report of board of inquiry into 275kV system fault on Saturday, November 85th, 1969

If you liked this: some videos

I really like this British Library film (YouTube) which shows the modern day control room, and the life stories of some control engineers.

The BBC film "The Secret Life of the National Grid" might be interesting - it's here (YouTube).

Galloping conductors (YouTube) shows a power line cables oscillating to the point of destruction due to wind.

Practical Engineering (YouTube) has a series explaining how the grid operates.

Update: 28 November 2025 - I uploaded some brochures to the Internet archive:

SSEB Grid control brochure 1972 and SSB Grid control brochure 1981

…and a video: